This pandemic has exposed the digital divide. While the findings from the simulations above largely play out along existing economic divides, access to digital technology has become another dimension of inequality. It operates in multiple ways. Firstly, teleworkers who can perform their jobs from home are more protected from the health risks of the pandemic. Data on morbidity and mortality rates related to COVID-19 in other countries show that essential workers, many in healthcare and retail, have been unduly affected. Secondly, these workers are more protected from job losses as many opera- tions can shift online, mitigating losses in earnings. Finally, access to digital technology at the household level has important implications for children’s ability to learn remotely. Prolonged school closures and a move to remote learning mean that children in homes with- out access to computers or tablets may fall behind. These education losses may compound over time leading to diverging trends along the digital divide.

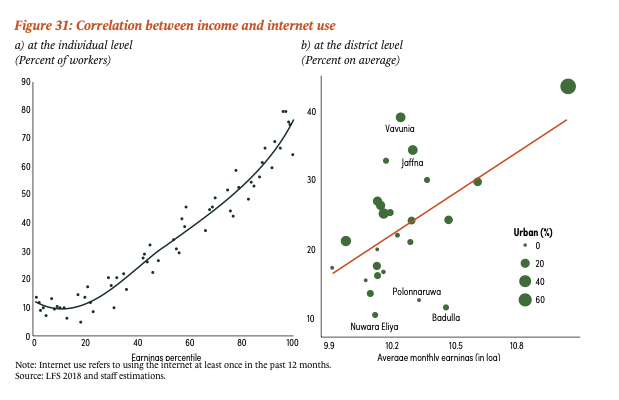

Wide inequalities in digital access could further aggravate eco- nomic and spatial inequality. Digital technology and the internet can act as driving forces of income convergence, both across individ- uals and across districts. However, if access is higher among richer households or in richer districts, digital technologies can compound existing inequalities. Digital access is higher for richer households (Figure 31a), so that it aggravates economic inequality and lowers economic mobility. In addition, the digital divide also has a geo- graphic dimension as richer and more urban districts have higher access to technology (Figure 31b).

Internet use is twice as prevalent in urban areas than in rural areas. In the former, four out of ten people used the internet at least once in 2018, relative to only two out of ten in rural areas. The high correlation between the differ- ent dimensions of inequality – economic, digital and spatial – make it unlikely that digital opportu- nities will have an equalizing impact without large policy intervention. One example is the impact of opportunities to work remotely.

Only high-income earners can benefit from working remotely.

The share of potential teleworkers in Sri Lanka can be estimated based on an established classification of the feasibility of working from home for different occupations (see Appendix A3). Around 27 percent of workers in Sri Lanka have potentially tele-workable jobs. Figure 32 shows that such job opportunities are much more com- mon among high-income earners. Among the highest 20 percent of income earners, the share of teleworkers is 47 percent. To be able to telework, one does not only need a job that allows for it, but also dig- ital access. Refining the share of teleworkable jobs – by controlling for the ownership of a digital device (desktop, laptop or tablet) and the ability to use it – widens the divide since many poor likely access the internet only through their mobile phones, if at all. Almost no one in the lower half of the income distribution can actually work from home and even among the higher-middle income earners the share is only around 10 percent. It is only among the highest income earners that the share reaches a third. While the share of potential tele-workers is on average only around 24 percent in rural areas, it is around 40 percent in Colombo. The possibility of remote work is also more common in some sectors of the economy than in others and is higher in the public than in the private sector. By offering greater employment opportunities and protections to these richer and more urban teleworkers, the digital divide widens existing eco- nomic and spatial inequalities.

Figure 32:

Adoption of telework and digital technology is higher for large private sector firms than for small and medium-sized enterprises. On the labor demand-side, a majority of leading private sector employers reported that flexible work policies were among the most useful for managing human resources during COVID-19. However, challenges in infrastructure and adapting jobs to a fully remote workplace remain. Low phone and internet connectivity were cited as the foremost reason for productivity dips among employees during the pandemic. Just as the amenability for telework varies across workers, the same applies to firms. Small and medium-sized enterprises, were unlikely to adopt digital technology during the lockdowns and women-owned enterprises even less so.

https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/15b8de0edd4f39cc7a82b7aff8430576-0310062021/original/SriLanka-DevUpd-Apr9.pdf

would enable you to enjoy an array of other services such as Member Rankings, User Groups, Own Posts & Profile, Exclusive Research, Live Chat Box etc..

would enable you to enjoy an array of other services such as Member Rankings, User Groups, Own Posts & Profile, Exclusive Research, Live Chat Box etc..

Home

Home

No Comment.