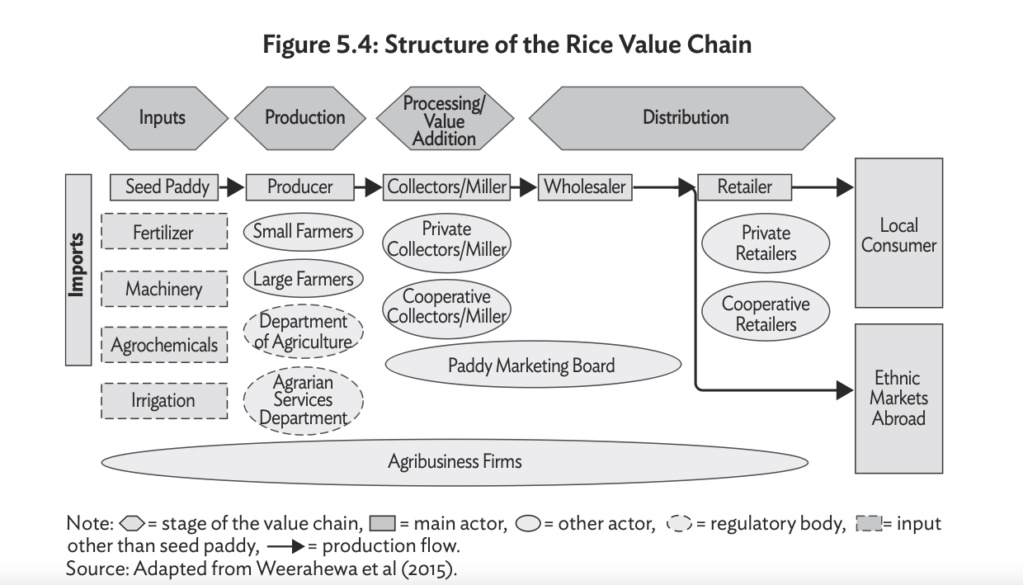

The rice value chain operates under a highly protected environment. The Paddy Marketing Board (PMB) was established in 1970 as the government-authorized body to purchase, sell, supply, and distribute paddy (unhulled rice) and to mill paddy and polish and prepare rice (PMB 2010). The PMB, a key actor in the value chain, was abolished in the early 1990s and reestablished in 2005. The PMB restarted purchasing paddy from farmers in 2008. The PMB also maintains a buffer stock of paddy (PMB 2010).1 However, the PMB is not as powerful in the rice value chain as it was in the 1970s and 1980s and large private rice millers now have more control over the rice stocks and prices than the PMB does (Figure 5.4). The rice value chain is characterized by a high concentration in rice milling.

The government used to be the main producer and supplier of seed to rice growers, but large agribusiness companies such as CIC Agribusiness and farmers have moved into seed production. With the development of agribusiness firms in Sri Lanka, rice out-grower systems were introduced to the rice value chain. The agribusiness firms grow special varieties of good quality rice for niche markets.

Sri Lanka is not competitive in the world rice market because of the high cost of production and lack of global consumer preference for the short-grain varieties preferred in Sri Lanka, although some traditional varieties of rice might find a niche abroad. Rice from Sri Lanka is exported to Sri Lankan communities living abroad.

Dairy Value Chain

The Sri Lankan government has a very ambitious target of becoming self- sufficient in milk. But at the rate the sector is growing (1%–2% per year), it will have difficulty meeting the increasing demand.

In 2015, 374 million liters of milk were produced domestically. Of the total production, about 75% was channeled domestically via informal routes (Vernooij et al., 2015) and consumed as fresh milk or processed into products such as curd and yoghurt. According to Vernooij et al. (2015), MILCO Pvt. Ltd (a government- owned company) is the largest collector and accounts for 30% of the milk collected in Sri Lanka. Other collectors include Nestle Lanka Pvt. Ltd. (which collects about 23% of the milk that enters the formal milk market); Pelwatta companies, Rich Life, Kothmale, Cargills, Fontera, Ambewella, and CIC. Altogether, large-scale producers’ collected 219 million liters of milk in 2015 (CBSL 2015), implying that approximately 60 million liters were channeled through small-scale collectors in the formal sector.

Domestic milk production is sufficient to meet only 40% of the requirement. In 2015, imports of milk and milk products increased. Sri Lankans are more used to drinking powdered milk than raw liquid milk, and 81,759 tons of milk powder were imported in 2015 (CBSL 2015).

Sri Lanka produces milk from dairy cattle and buffalo. In 2015, dairy cows produced 305 million liters of milk and buffalo produced 69 million liters. Sri Lanka had 392,710 milking cows and buffalo (91,570 were buffalo). Large-scale collectors accounted for 219 million liters. Government-owned farms produced 11 million liters in 2015. During 2012–2013, the government farms imported 2,000 cows from Australia; their output also helped meet the industrial demand for liquid milk.

Milk is produced in all Sri Lanka’s districts. The largest cattle populations are in the dry and intermediate ecological zones. In terms of production, wet mid- and up-country areas are often perceived as the main dairy-producing areas. However, the dry and dry-intermediate zones produce 50% more milk than the wet and wet-intermediate zones. In the formal milk collecting network, 300,000 liters are channeled every day. However, the collecting network’s capacity remains underutilized.

Most milk is coming from smallholders who keep 1–2 cows. Cattle are raised mostly by smallholders as part of crop–livestock integration. The smallholder’s milk production is low as the cattle are not fed high-quality grass and concentrates. Because the financial return for the farmers’ labor is less than 50% of the casual wage rate, it is difficult to retain farmers in dairy production. Similar smallholder systems in Kenya and India are 50%–70% more productive than those in Sri Lanka, because the costs are lower than in Sri Lanka due to lower wage rates and cheaper feed. Milk production could be improved by attaching large-scale dairy farms and smallholders through an out-grower system, which has been successful in in Sri Lanka’s poultry industry.

The efficiency of the dairy value chain (Figure 5.5) is hindered by the limited availability of good quality grass and limited awareness of good management practices.

Vegetable Value Chain

Vegetables are cultivated both in the uplands and in the plains, each with weather conditions suitable for different types of vegetables. Upland vegetable cultivation (mainly in Bandarawela, Nuwara-Eliya, and Welimada areas) is considered to be highly intensive with significant use of agrochemicals, whereas cultivation in the plains is less intensive and uses fewer chemicals. Vegetable farms sell their produce to village or town traders. The traders transport the produce to (1) large markets in Colombo, which distribute to the entire country; or (2) dedicated economic centers established in other parts of the country, which distribute vegetables grown near them.

Figure 5.6 depicts the vegetable supply chain. A new supply chain emerged with the spread of supermarkets, which sell produce for high-end, quality conscious customers. Small- and medium-scale supermarkets have become large buyers from wholesale vegetable suppliers in the traditional supply chain. Large supermarket chains have established procurement centers that buy directly from the farmers. This is more efficient than using the traditional supply chain because direct purchasing can reduce post-harvest losses due to improper harvesting practices and handling and to poor conditions during transport. Supermarket chains that buy directly from farmers promise to grade vegetables and pay a premium for high quality. However, this practice is not strictly implemented in all the procurement centers. Nevertheless, post-harvest losses are lower in the vegetables that pass through the supermarket procurement centers to the customers, as supermarkets are capable of adopting good handling practices.

The effects of supermarkets on consumer prices, producer prices, and food quality have been examined by a number of authors. Abeysekera and Abeysekera (undated) revealed that retail prices in supermarkets are 10%–15% lower than those in conventional marketing chains, contract growers supplying vegetables to the supermarkets receive prices that are 15%–25% higher than through the conventional marketing system, and most supermarkets have taken several steps to ensure the quality and improve the shelf life of fruits and vegetables. According to Kodithuwakku and Weerahewa (2013), supermarkets had created an alternative supply chain of vegetables that was more efficient and effective than traditional supply chains in terms of transparency, accountability, number and role of intermediaries, and prevalence of quality consciousness throughout the supply chain, as well as resulting in comparatively low post-harvest losses. However, only a minority of farmers had direct access to this supply chain.

Some supermarkets have developed contract grower systems for vegetables. The emergence of the supermarkets’ supply chains has increased competition for supply and diverted some farmers’ focus from traditional agriculture to alternative crops. However, the volume of vegetables flowing through the supermarket supply chain is smaller than through the traditional value chain, which remains the most assured market for farmers despite its weaknesses.

Vegetable value chains are impacted by farmers’ inadequate awareness of good agricultural practices; a large number of intermediaries, which inhibits the efficiency of passing through quality signals; and inadequate links with foreign buyers.

Fish Value Chain

Although marine fisheries have expanded and increased production substantially over the years, local fish prices remain high compared with peoples’ average incomes, and the fishing communities’ living standards have not improved much. One reason is that fisher families depend on local assemblers and commission agents, which hinders the fishers’ independent growth and progress. The commission agents enjoy enormous power partly because they assume high risk with respect to the degradation of product quality (spoilage) and have access to market links and information. Commission agents invest fuel and food in fishing trips without assurance of a good fish catch.

Therefore, fishers are highly dependent on the commission agents. Fishers could have a larger share of their catches if they directly interacted with exporting companies and large retailers. The United Nations Environment Programme (2009) showed that when fishers organize as groups for making collective decisions, the result can be more efficient and fairer value chains. To be effective, fisher cooperatives need guidance and monitoring by the government or another authority. The fish value chain is shown in Figure 5.10.

Most fish is exported whole or after minimal processing. If more fish can be exported as processed products with greater value added, more employment and foreign exchange would result. The fishers need education in proper fish handling and the importance of hygienic conditions to maintain the quality of fish along the supply chain, especially for the quality-conscious export market. The domestic consumer market responds more to price than quality. Consumer awareness of the importance of quality in fish needs to be improved. If the currently hierarchical value chain could be flattened, the intermediaries’ exorbitant margins could be reduced and the benefits shared by fishers and consumers.

Tea Value Chain

Figure 5.9 illustrates Sri Lanka’s tea value chain. Almost all tea (96%) is marketed through public auction. Sri Lanka receives a higher price for its black tea in auctions in Colombo than other producers receive in their auctions (in Chittagong, Cochin, Guwahati, Jakarta, Kolkata, Malavi, and Mombasa). The main importers of bulk Sri Lankan black tea by import volume are Turkey, the Russian Federation, Iran, Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, and Syria.

Prices received for tea vary according to the elevation at which it is grown. The uplands were previously considered to produce the best quality tea and hence received the highest price. However, during the last decade, tea from the plains has received higher prices than that from the uplands, and in 2015 received the highest price followed by tea growing in Nuwara-Eliya (uplands).

In the plains, tea is mainly grown by smallholders, and smallholder production has increased while plantation production has stagnated. Upland tea plantations usually comprise a tea factory where green tea is fermented to black and then sent directly to auction. Smallholder tea growers collect and sell green tea leaves directly to the factories. Home-garden tea growers sell leaves to collectors or a nearby plantation.

Sri Lankan tea exports have benefited vastly from the rapid and direct shipping connection to most of its large tea exporters. Because Sri Lanka has been exporting tea for centuries, its auction process and exporting have become very efficient. One reason for high auction prices in Colombo is the fast shipping connections. However, Sri Lanka’s cost of producing tea has increased more than that of its competitors, mainly due to the labor cost for harvesting tea. Large plantations have difficulty hiring skilled harvesters at low wage rates. This is less of a problem for small-scale tea growers as they can use family labor. Sri Lanka’s yield per harvester (18 kilograms [kg] per day) is below that of Kenya (46 kg per day) and India (25 kg per day).

Coconut Value Chain

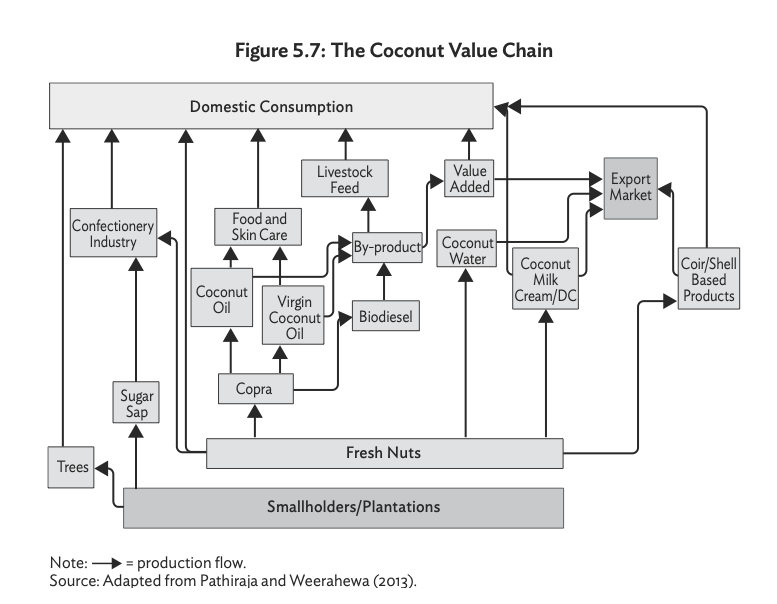

The coconut value chain (Figure 5.7) includes several types of items—food products, such as raw coconut, oil, and coconut milk; products from coconut waste, such as coconut fibers and shells; and crops that are intercropped with coconut, such as banana and rambutan. Stakeholders in the Sri Lankan coconut value chain are the growers, desiccated coconut millers, copra manufacturers, coconut oil manufacturers, fiber millers, shell charcoal manufacturers, value- added fiber product manufacturers, activated carbon manufacturers, and exporters (EDB 2012).

Producers generally have a poor understanding of the market (Romulo 2013). Infrastructure for manufacturing and transporting coconut products is insufficient. A major constraint that desiccated coconut exporters face is inadequate production to feed the mills. Additionally, the industry faces increasing energy costs and has not innovatively expanded its supply of products.

Coconut plantations are being fragmented and farmers practice intercropping with coconut to increase returns from the land. Links between smallholder farmers and processors are weak.

would enable you to enjoy an array of other services such as Member Rankings, User Groups, Own Posts & Profile, Exclusive Research, Live Chat Box etc..

would enable you to enjoy an array of other services such as Member Rankings, User Groups, Own Posts & Profile, Exclusive Research, Live Chat Box etc..

Home

Home

No Comment.