The shift toward goods consumption, particularly in advanced economies, overloaded global supply chain networks during the pandemic. This problem was compounded by pandemic-related impediments to transportation and staffing, as well as by the inherently fragile nature of just-in-time

logistics and lean inventories. The resulting disruption to global trade led to shortages and higher prices for imported consumer goods.

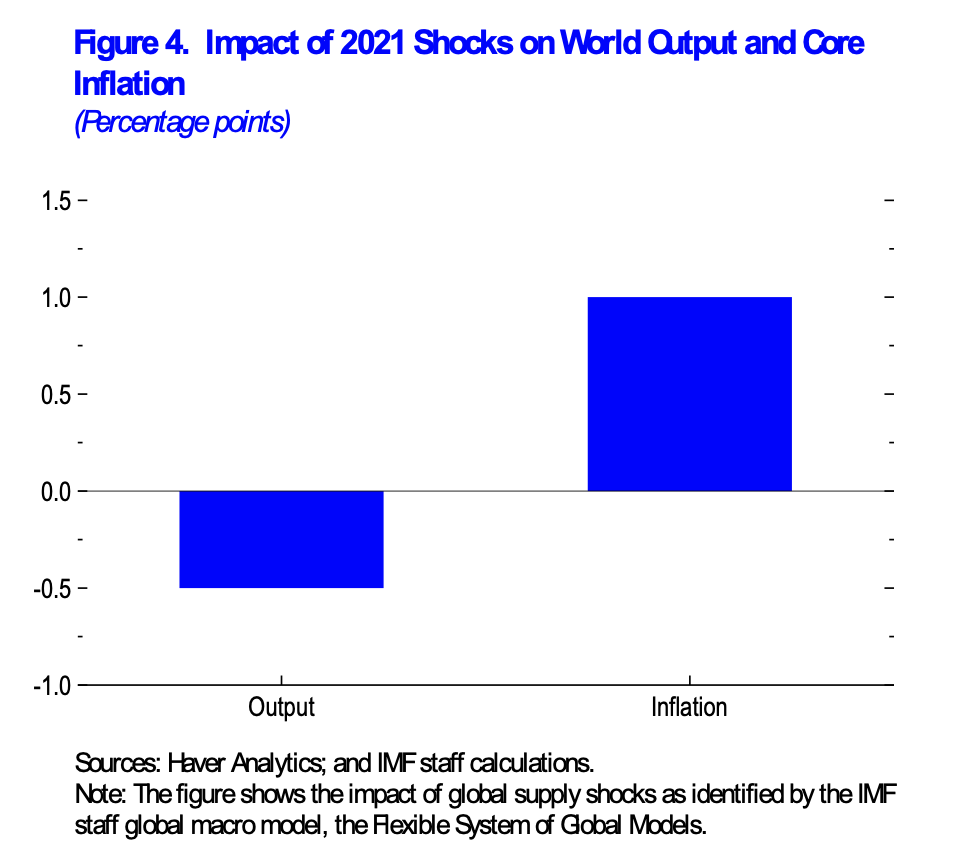

Disruptions in the United States have been particularly severe, consistent with the larger switch into goods consumption. IMF staff analysis suggests that supply disruptions shaved 0.5–1.0 percentage point off global GDP growth in 2021 while adding 1.0 percentage point to core inflation.

Although international shipping fleets have limited spare capacity, the bottlenecks are often on land, with trucking and other services unable to move freight off the docks faster than new ships can bring it in.

These supply chain disruptions will eventually ease, not least because the composition of demand is likely to shift back to services (households can buy only so many durable goods). The baseline assumes supply-demand imbalances will wane over the course of 2022. But the longer they persist, the more likely they are to feed through to expectations of higher future prices and the larger the risk to the world economy.

Dysfunctional global supply chains also leave economies less able to adapt to a possible resurgence of the pandemic, as clogged ports impede the flow of goods needed to adapt to changing public health conditions. The impact of the Omicron variant may further limit the efficiency of ports, add to shipping problems, and delay the rebalancing of consumer demand from goods to services—thus exacerbating supply-demand imbalances.

would enable you to enjoy an array of other services such as Member Rankings, User Groups, Own Posts & Profile, Exclusive Research, Live Chat Box etc..

would enable you to enjoy an array of other services such as Member Rankings, User Groups, Own Posts & Profile, Exclusive Research, Live Chat Box etc..

Home

Home