Banks are susceptible to a range of risks. These include credit risk (loans and others assets turn bad and ceasing to perform), liquidity risk (withdrawals exceed the available funds), and interest rate risk (rising interest rates reduce the value of bonds held by the bank, and force the bank to pay relatively more on its deposits than it receives on its loans).

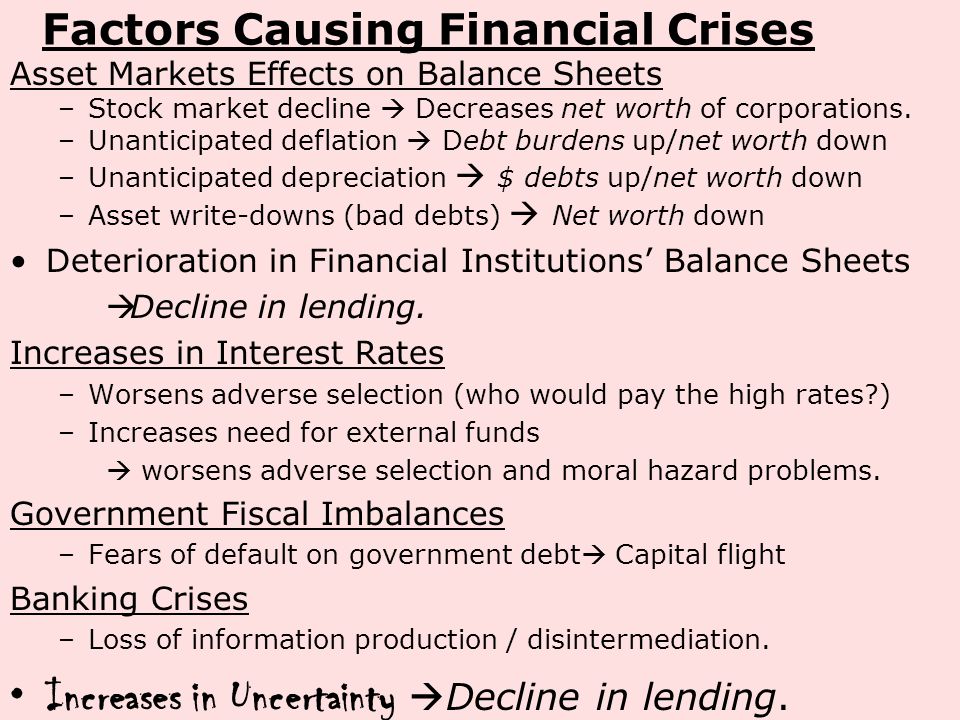

Banking problems can often be traced to a decrease the value of banks’ assets. An deterioration in asset values can occur, for example, due to a collapse in real estate prices or from an increased number of bankruptcies in the nonfinancial sector. Or, if a government stops paying its obligations, this can trigger a sharp decline in value of bonds held by banks in their portfolios. When asset values decrease substantially, a bank can end up with liabilities that are bigger than its assets (meaning that the bank has negative capital, or is “insolvent”). Or, the bank can still have some capital, but less than a minimum required by regulations (this is sometimes called “technical insolvency”)

Bank problems can also be triggered or deepened if a bank faces too many liabilities coming due and does not have enough cash (or other assets that can be easily turned into cash) to satisfy those liabilities. This can happen, for example, if many depositors want to withdraw deposits at the same time (depositor run on the bank). It can also happen also if the bank’s borrowers want their money bank and the bank does not have enough cash on hand. The bank can become illiquid. It is important to note that illiquidity and insolvency are two different things. For example, a bank can be solvent but illiquid (that is, it can have enough capital but not enough liquidity on its hands). However, many times, insolvency and illiquidity come hand in hand. When there is a major decline in asset values, depositors and other banks borrowers often start feeling uneasy and demand their money bank, deepening the bank’s troubles.

A (systemic) banking crisis occurs when many banks in a country are in serious solvency or liquidity problems at the same time—either because there are all hit by the same outside shock or because failure in one bank or a group of banks spreads to other banks in the system. More specifically, a systemic banking crisis is a situation when a country’s corporate and financial sectors experience a large number of defaults and financial institutions and corporations face great difficulties repaying contracts on time. As a result, non-performing loans increase sharply and all or most of the aggregate banking system capital is exhausted. This situation may be accompanied by depressed asset prices (such as equity and real estate prices) on the heels of run-ups before the crisis, sharp increases in real interest rates, and a slowdown or reversal in capital flows. In some cases, the crisis is triggered by depositor runs on banks, though in most cases it is a general realization that systemically important financial institutions are in distress.

Systemic banking crises can be very damaging. They tend to lead affected economies into deep recessions and sharp current account reversals. Some crises turned out to be contagious, rapidly spreading to other countries with no apparent vulnerabilities. Among the many causes of banking crises have been unsustainable macroeconomic policies (including large current account deficits and unsustainable public debt), excessive credit booms, large capital inflows, and balance sheet fragilities, combined with policy paralysis due to a variety of political and economic constraints. In many banking crises, currency and maturity mismatches were a salient feature, while in others off-balance sheet operations of the banking sector were prominent.

A global database of banking crises was first compiled by Caprio and Klingebiel (1996). The latest version of the database, updated to reflect the recent global financial crisis, is available as Laeven and Valencia (2012). It identifies 147 systemic banking crises (of which 13 are borderline events) from 1970 to 2011. It also reports on 218 currency crises (defined as nominal depreciation of the currency vis-à-vis the U.S. dollar of at least 30 percent that is also at least 10 percentage points higher than the rate of depreciation in the year before) and 66 sovereign debt crises (defined by government defaulting on its debt to private creditors) over the same period. The database has detailed information about the policy responses to resolve crises in different countries. Analyses based on the dataset, such as Cihák and Schaeck (2010) suggest that consistently predicting banking crises is very difficult, but there are some variables (such as those capturing high leverage and rapid credit growth) that indicate increased likelihood of a crisis.

https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/gfdr/gfdr-2016/background/banking-crisis

What Triggers a Systemic Banking Crisis?

A systemic banking crisis is one in which all or substantially all of the banking capital in a country is wiped out. You might have expected that such crises would be rare events, but researchers at the World Bank have compiled a listing of 113 such crises in 93 countries during 1975-1999. They are nearly universal, hugely expensive and should be a public policy issue of the first magnitude. Never before in history have banking crises been so frequent or so devastating.

In general, such crises go through two phases. In the first or silent phase, banks make a great many bad loans, for any number of reasons alone or in combination, and consequently develop a large number of non-performing loans (NPLs) on their balance sheets. Generally these are not publicly acknowledged nor reported; they simply build up, quietly destroying the banks' capital base. Then in the second or critical stage it is publicly acknowledged that the banks are insolvent and agents take action to remedy the situation as best they can.

The two-phase structure arises because governments typically protect banks by guaranteeing their deposits and often by concealing the depth of their problem loans. In principle, a government can go on doing this for a very long time - so long as the government's credibility is not in doubt, people will continue to hold government-guaranteed deposits. So the question arises, why does the first phase ever give way to the second? What finally triggers the crisis? This is an important question for those eager to spot the next crisis or to assess the financial stability of countries.

The author's answer is that any one of four agents can trigger the crisis: depositors, government, external lenders and intergovernmental financial institutions, because each is a supplier of bank funding. To put it simply, the crisis is triggered when a significant funder withdraws support. This paper reviews the entire list of 113 crises and classify them according to their triggering events. Depositors can trigger the crisis in those situations where the government's deposit guarantee is either flawed or loses credibility. The government itself may trigger the crisis at any significant regime change, so that the previous regime can be blamed for the problem. External lenders can trigger the crisis whenever the banking system is significantly dependent on external funding; for example, the East Asia crisis of 1997-98 can be viewed as a run on Asian banks by international banks. Finally, intergovernmental financial institutions such as the World Bank and IMF (which often work in concert) can trigger the crisis for any country significantly dependent on their funding.

https://www0.gsb.columbia.edu/mygsb/faculty/research/pubfiles/196/Banking_Crises.pdf

would enable you to enjoy an array of other services such as Member Rankings, User Groups, Own Posts & Profile, Exclusive Research, Live Chat Box etc..

would enable you to enjoy an array of other services such as Member Rankings, User Groups, Own Posts & Profile, Exclusive Research, Live Chat Box etc..

Home

Home

No Comment.