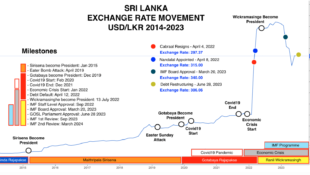

Domestic Debt Restructuring

DDR in Sri Lanka is complicated by the large holdings of rupee debt by financial institutions such as banks. As Sri Lanka’s banks are heavily dependent on income from coupon payments on rupee bonds (around 36% of their income arises from government securities, and this income is used to pay the interest on deposits and savings of the public), it would not be advisable to implement a reduction in the coupons. Consequent to a DDR that extends the maturity of domestic debt, financial institutions may need additional capital. However, temporary regulatory forbearance till yields return to lower levels can delay the need and size of the recapitalisation that will be needed.

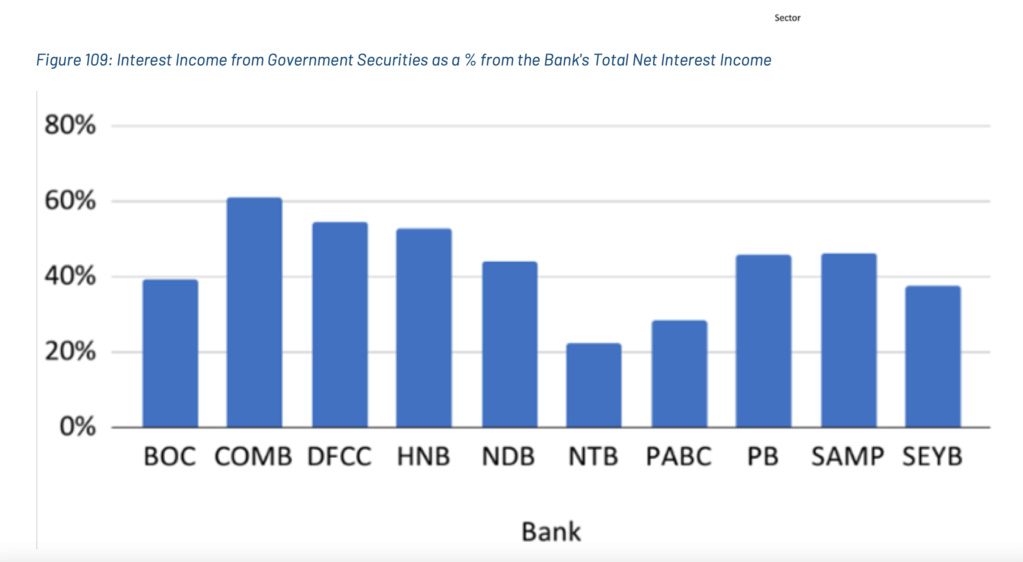

Interest Income from Government Securities as a % from the Bank's Total Net Interest Income

Above figures show that on average 36% of the net interest income of major banks is from government securities. Any cut on coupons will adversely affect the profitability of the banking sector — hence maintaining coupons will be necessary to maintain financial sector stability.

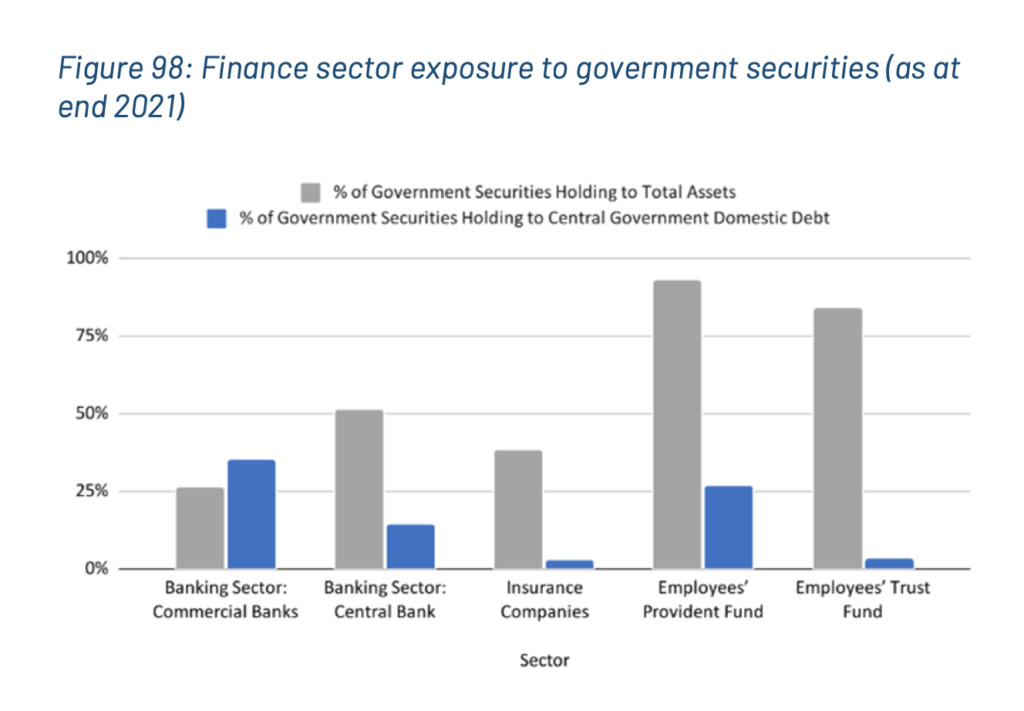

By 2021 end, the Sri Lankan banking sector had Rs. 19.98 trillion in assets, which is 64% of the financial sector’s total assets excluding the Central Bank. The Licensed Commercial Banks (LCBs) dominate the sector holding 55.4% of total assets.

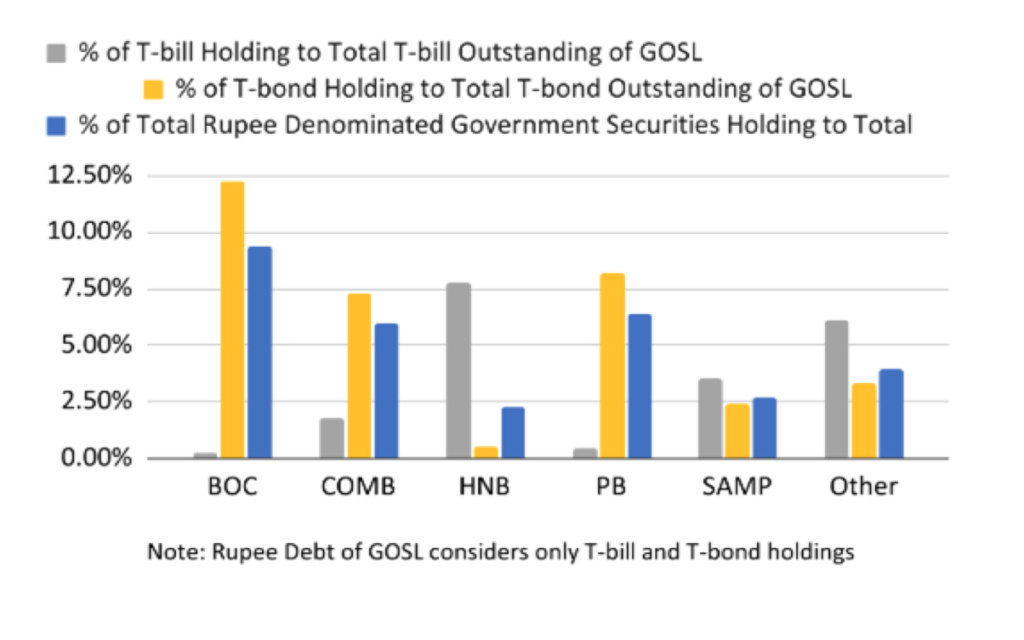

Domestic commercial banks and their subsidiaries (excluding Cargills Bank) were holding an average of 26% in government securities from their total assets of which 79% accounted for rupee denominated debt. Here we refer to government securities as T-Bills, T-Bonds, Sri Lanka Sovereign Bonds (SLSBs) and Sri Lanka Development Bonds (SLDBs), where SLSBs and SLDBs are dollar denominated.

Comparing the above figures with the total outstanding T-Bills and T-Bonds by end 2021 payable by the central government, our calculations show these banks together hold up to 31% of their assets.

Finance sector exposure to government securities (as at end 2021)

Public, or government, debt falls into three broad categories: external (foreign currency denominated) debt or loans owed directly by the government, domestic (domestic currency, here rupee) debt owed directly by the government and debt (or loans) owed by government-owned institutions and enterprises (which can be external and/or domestic). Sri Lanka is currently at a public debt to GDP ratio of around 121%, well above the ceiling of 80% recommended by the IMF. Restructuring external debt owed by the government only provides limited relief. External debt held by bondholders (ISBs/SLDBs) constitutes 20% of GDP, while loans to the government by multilateral and bilateral lenders are 32%. Multilateral and bilateral lenders are more likely to extend the maturity of their loans, or provide other grants or subsidies, than reduce the amounts outstanding on their loans. Furthermore, renegotiating external debt, obtaining bridging finance and receiving financial assistance from multilateral lenders such as the IMF are moot if the government has no viable path to solvency.

The present analysis, based on data up to July 2022, suggests that even with a principal cut (haircut) on ISBs/SLDBs of 50% and a 25% haircut on multilateral/bilateral loans, the projected debt to GDP of Sri Lanka will rise to 136% within 10 years at current yields. The same projections show that if in addition to external debt restructuring, there is a 10-year maturity extension (but no coupon or principal cut on domestic Treasury Bonds), debt to GDP will rise to only 101% in the next 10 years, even at the current yield curve. This leads to the conclusion that restructuring domestic debt would represent an immediate and significant improvement in the sustainability of Sri Lanka’s debt.

BY VERITÉ RESEARCH SRI LANKA POLICY GROUP

https://www.veriteresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/VR_EN_BN_Oct2022_The-Desirability-of-Domestic-Debt-Restructuring.pdf

would enable you to enjoy an array of other services such as Member Rankings, User Groups, Own Posts & Profile, Exclusive Research, Live Chat Box etc..

would enable you to enjoy an array of other services such as Member Rankings, User Groups, Own Posts & Profile, Exclusive Research, Live Chat Box etc..

Home

Home